As the effects of climate change become harder to ignore, finding ways to act sustainably has never become more important. However, despite the pressing need to act more pro-environmentally, many individuals still struggle to translate their environmental worry into action. If we know what we need to do to act more sustainably and keep our planet green, why don’t we do it?

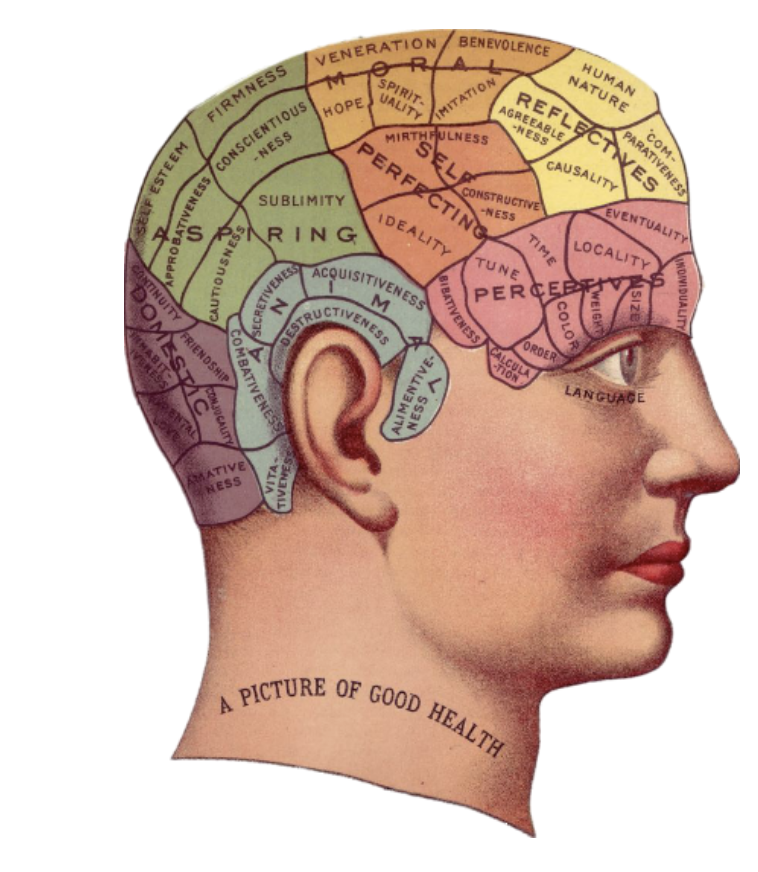

Dr. Robert Gifford from the University of Victoria suggests that one’s motivation to act sustainably can be impacted by seven psychological barriers, which has been referred to as the dragons of inaction. To understand how wanting to act pro-environmentally does not translate into action, one of the seven barriers of inaction will be discussed – limited cognition. Limited cognition refers to our brain’s inability to fully grasp the reality of climate change because of various cognitive factors such as ancient brain, ignorance, and uncertainty.

Ancient Brain. Although humans have evolved and made incredible societal and technological advances over the last thousands of years, the ancient brain our ancestors had and the brain we have today are not so different. Thousands of years ago, our ancestors exploited environmental resources to survive and were more concerned about making it through the day rather than the welfare of the planet. In present day, our population has grown exponentially, and we are not as worried about survival. However, despite our circumstances changing, our priorities have not, and we are still exploiting the planet’s resources, which has become unsustainable. Since our brain is programmed to focus on the present, we are less inclined to consider how exploiting resources will affect our future. Although we know we should be acting in more sustainable ways, our brain is wired to focus on the now, which could make environmental action more difficult.

Ignorance. Another cognitive limitation is ignorance, according to Dr. Robert Gifford. Ignorance involves either not knowing that there is a problem, or not knowing what to do when the problem becomes known. In relation to climate change, some people may not be aware of climate change, or do not know how to take action. The research available for those who do want to learn about climate change can involve much jargon, contain mixed messages that can be confusing, and create uncertainty rather than motivation. With all of this information, it can be challenging to know what to do, which can make acting sustainably more difficult.

Optimism Bias. Although there are many cognitive limitations that can affect our ability to act sustainability, the last limitation that will be discussed is optimism bias. Being optimistic is important to feeling like the world isn’t doom and gloom, and life is meaningful. However, being optimistic about climate-change can downplay the environmental consequences of inaction and make acting sustainably seem less important than it is. The rose-coloured glasses many people have surrounding climate change may make people think that things are better than they seem, which may cause engaging in environmental behaviours seem less pressing and result in less environmental action.

Climate change is a complex problem that requires the human race to work together to fix. Just because we have cognitive limitations does not mean we cannot overcome them and build a better future. Being aware of these cognitive limitations we have is the first step to working towards changing our environmental worries, into environmental action.

is a second-year Masters student who is interested in how psychological well-being can be impacted by different social and environmental factors, such as spending time in nature.Anna is also interested in why individuals may be more motivated than others to engage in pro-environmental behaviours, and how environmental behaviours are linked to well-being.

References

Bord, R. J., O’Connor, R. E., & Fisher, A. (2000). In what sense does the public need to understand global climate change? Public Understanding of Science, 9(3), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-6625/9/3/301

Gifford, R. (2011). The Dragons of Inaction: Psychological Barriers That Limit Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. American Psychologist, 66(4), 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/A0023566

Gifford, R., Scannell, L., Kormos, C., Smolova, L., Biel, A., Boncu, S., Corral, V., Güntherf, H., Hanyu, K., Hine, D., Kaiser, F. G., Korpela, K., Lima, L. M., Mertig, A. G., Mira, R. G., Moser, G., Passafaro, P., Pinheiro, J. Q., Saini, S., . . . Uzzell, D. (2009). Temporal pessimism and spatial optimism in environmental assessments: An 18-nation study. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.06.001

Ornstein, R. E., & Ehrlich, P. R. (2000). New world new mind: Moving toward conscious evolution. ISHK.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

Additional Resources

Gifford, R. (2023). The dragons of inaction. WordPress. https://www.dragonsofinaction.com/limited-cognition/

Tedx Talks. (2020). The psychology of Climate change – Shanlea Tabofunda. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9dZgJt0R-DU

Tedx Talks. (2015). Your brain on climate change – JC Kibbey. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rGKVjZ7Dy5E

Harman, G. (2014). Your brain on climate change: Why the threat produces apathy, not action. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2014/nov/10/brain-climate-change-science-psychology-environment-elections